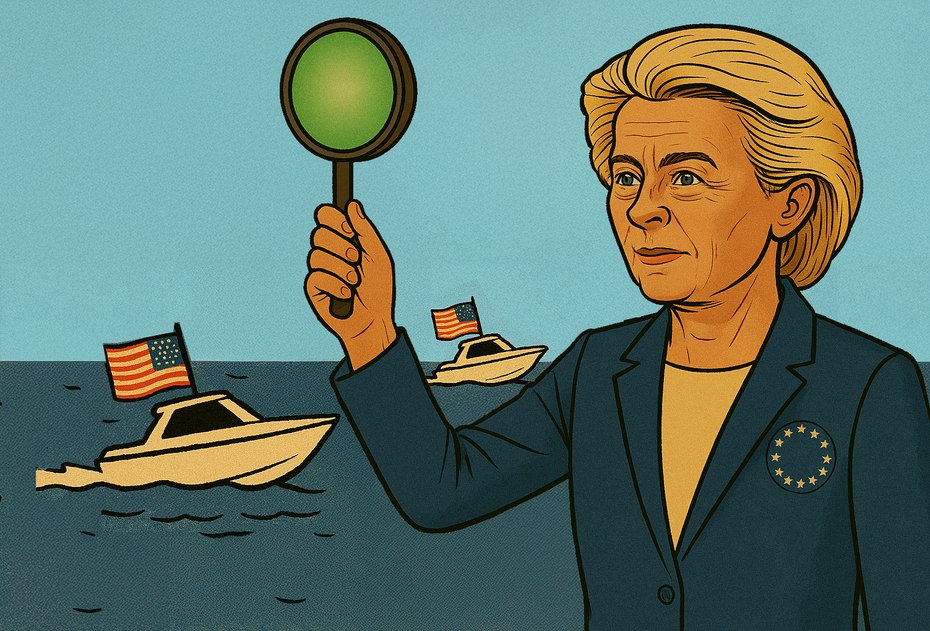

The case, filed by Ya Mon Expeditions, LLC and a group of used yacht sellers, accused several prominent brokerage associations and multiple listing services (MLS) of violating antitrust laws by maintaining an industry-standard 10% commission rate and barring “For Sale by Owner” (FSBO) listings.

The lawsuit, which was consolidated from multiple cases, alleged that brokers and trade groups used their dominant market position to enforce inflated fees and limit competition. Plaintiffs argued that the industry’s structure, codes of conduct, and use of uniform listing agreements effectively locked out unrepresented sellers, forcing them to pay inflated brokerage fees.

Court’s Decision

U.S. District Judge K. Michael Moore granted the defendants’ motion to dismiss the case, ruling that the plaintiffs failed to provide sufficient evidence of a conspiracy or illegal coordination under the Sherman Antitrust Act.

The Complaint merely points to suggestions, general practices, and industry norms to satisfy the conspiracy element of Section One claims. This is insufficient to plausibly allege an agreement or conspiracy under antitrust law.

The court rejected the claim that the yacht brokers engaged in unlawful collusion, citing a lack of direct or circumstantial evidence. While the plaintiffs pointed to industry norms in the sales process of sailing and motor yachts and non-binding trade association guidelines as evidence of coordination, the court concluded that these practices could equally be attributed to independent business decisions.

Judge Moore noted that the plaintiffs had not identified any binding rules requiring sellers to pay fixed commission rates or brokers to refuse FSBO listings. The court also emphasized that participation in trade associations, by itself, is not evidence of collusion unless accompanied by proof of an actual agreement to restrain trade.

Parallel Case Comparison

The plaintiffs attempted to draw parallels to a similar lawsuit in the real estate industry, Moehrl v. National Association of Realtors, where centralized rules for commission-sharing were found sufficient to allege a conspiracy. However, the court found the comparison unpersuasive, noting significant differences in the structure of the yacht brokerage industry. Unlike the real estate case, the yacht industry lacks a single, centralized trade association with binding rules governing commissions.

Next Steps for Plaintiffs

The dismissal was issued without prejudice, meaning the plaintiffs have 21 days to amend and refile their complaint. The ruling leaves the door open for plaintiffs to provide additional evidence or refine their legal arguments to address the deficiencies identified by the court.

Implications for the Yacht Brokerage Industry

The decision is a significant victory for the yacht brokerage industry, which argued that its practices reflect standard, independent business decisions rather than anticompetitive conduct. Defendants welcomed the ruling, stating that the case lacked merit and failed to demonstrate any harm to competition.

Broader Context

The lawsuit comes amid heightened scrutiny of commission structures in various industries, including real estate and technology. Antitrust enforcement has been a growing focus for regulators and private plaintiffs seeking to challenge practices that may harm consumers or stifle competition.

Whether the plaintiffs will choose to refile or appeal remains uncertain, but for now, the yacht brokerage industry can claim a legal victory in this high-profile case.